Spice Route Legal

Out and Back Again: The Legal Realities of Startup Reverse Flips

Introduction

Over the past decade, the Indian startup ecosystem has witnessed a fascinating trend — companies that once moved their corporate headquarters overseas, are now contemplating or actively pursuing a return to India. This phenomenon, commonly known as a “reverse flip” has sparked considerable interest amongst founders, investors, dealmakers and other stakeholders in the startup ecosystem.

A “flip” refers to the restructuring process where an Indian startup sets up a foreign holding company, often in a jurisdiction that offers investor-friendly regulations, access to global capital and favorable tax regimes, and moves its primary ownership and intellectual property abroad. This was particularly prevalent during the boom years of Indian startups seeking global venture capital and listing opportunities. However, reverse flipping, or the process of bringing the holding structure back to India, is emerging as a counter-trend, driven by a confluence of legal, regulatory, economic, and strategic factors.

What were the primary reasons for Indian companies to flip, and why are they now reverse flipping?

Historically, several factors pushed Indian startups to flip their operations to foreign jurisdictions. Foreign investors, particularly venture capital and private equity funds based in the United States and Singapore, preferred investing in offshore entities. These jurisdictions were perceived as offering tax incentives, ease of doing business, robust intellectual property protection and a more scalable framework for international expansion. Moreover, the long-standing ambition of Indian startups to list on global stock exchanges such as NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange also contributed to the trend. Additionally, India’s regulatory and tax landscape was often viewed as complex and restrictive, posing hurdles for global expansion.

Today, a growing number of Indian startups are reassessing their offshore holding structures and opting to relocate back to India. This shift is driven by multiple factors. The maturation of India’s capital markets, coupled with regulatory advancements like the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) in GIFT City, has created viable domestic avenues for fundraising and listing. Simultaneously, government initiatives such as Startup India, Production Linked Incentive schemes, and increased digitisation have incentivised local incorporation. On the global front, heightened geopolitical tensions and increased regulatory scrutiny in jurisdictions like the United States of America and China have made foreign domiciles less appealing.

Moreover, the costs and compliance burdens of maintaining offshore entities can be significant, particularly for the startups with limited international operations. With core functions, teams and customer bases often still rooted in India, operating from an Indian domicile simplifies taxation, employment and contractual arrangements. Investor sentiment also plays a pivotal role — many Indian venture capitalists and family offices now prefer domestic structures, especially as the Indian stock exchanges become more viable exit routes through listing with Indian stock exchanges.

How do you reverse flip?

Reverse flipping is a complex and a highly regulated process, involving multiple jurisdictions. There are different ways in which one can achieve the move back to India, some of which are set out below:

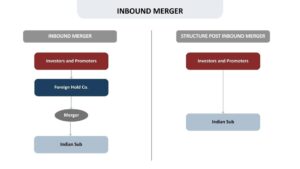

Inbound Merger

In an inbound merger, the foreign holding company (“Foreign Hold Co.”) merges with its Indian subsidiary (“Indian Sub”), resulting in the Indian Sub being the surviving entity, absorbing the Foreign Hold Co. and its operations. Pursuant to the merger, the shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. are issued shares by the Indian Sub, thereby becoming shareholders of the Indian Sub.

To effectuate an inbound merger, the parties would have to obtain the approval of the Reserve Bank of India. Owing to an amendment introduced by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs in September 2024, a merger between a foreign holding company and an Indian subsidiary is now allowed to be undertaken by way of fast track merger. What used to be a cumbersome and a time consuming process, which required the parties to obtain an approval from the National Company Law Tribunal, can now be achieved by taking approval from the Central Governmental, through the relevant Regional Director.

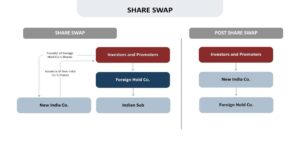

Share-Swap

Under this structure, the promoters incorporate a new company in India (“New India Co.”). The shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. would then swap their shares with the shares of the New India Co., resulting in the shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. becoming the shareholders of the New India Co. and the Foreign Hold Co. becoming a subsidiary of the New India Co.

Post the completion of the share swap, the Foreign Hold Co. is liquidated in accordance with the laws of the jurisdiction where the Foreign Hold Co. is incorporated, and the assets and the proceeds get distributed amongst the creditors, shareholders and other stakeholders, in accordance with the applicable laws.

Buyback or redemption of shares

In this structure, the Foreign Hold Co. uses the proceeds available with it to buyback or redeem the shares held by the shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. Pursuant to the buyback or redemption of shares by the Foreign Hold Co., the shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. infuse the cash in the Indian Sub, in a manner such that their shareholding in the Indian Sub is replicated with their shareholding in the Foreign Hold Co.

While this method offers high flexibility, it may involve tax leakages for the shareholders. Further, distribution of proceeds by the Foreign Hold Co. to its shareholders may involve careful structuring in accordance with the laws of applicable jurisdictions, on account of the complexities involved.

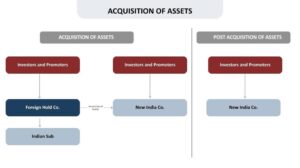

Acquisition of assets

This structure involves the promoters setting up a New India Co., and the shareholders of the Foreign Hold Co. subscribing to the shares of the New India Co. in a manner such that their shareholding in the New India Co. is mirrored with their shareholding in the Foreign Hold Co.

Subsequently, the New Indian Co. will acquire the assets of the Foreign Hold Co. and the Indian Sub. To finance this acquisition, funds may be infused into the New India Co. by way of equity, debt, or structured arrangements. Post the completion of the acquisition, the Foreign Hold Co. is liquidated in accordance with the laws of the jurisdiction where the Foreign Hold Co. is incorporated.

This approach may be simpler in terms of corporate restructuring but could give rise to tax and regulatory issues related to the transfer of intellectual property, contracts and data, and may not be viewed as a true continuation of the original business unless carefully structured and executed. This structure may also have to be evaluated in light of the nature of the assets to be acquired by the New India Co. from the Foreign Hold Co. in light of the regulatory restrictions and implications.

Key legal and regulatory considerations

While there are multiple legal pathways for executing a reverse flip, each structure must navigate a common set of critical considerations. These include taxation (both domestic and international), compliance with Indian foreign exchange regulations and adherence to the legal requirements of the foreign jurisdiction in which the holding company is incorporated. The success and efficiency of a reverse flip depends on how well these cross-cutting issues are anticipated and managed.

Taxation is one of the most significant drivers and potential hurdles in a reverse flip. The nature of the transaction will determine whether capital gains, dividend distribution tax, or transfer pricing provisions are triggered. Capital gains tax may apply to shareholders receiving shares or cash in exchange for their holdings in the foreign entity. If the structure involves a transfer of business or intellectual property to the Indian entity, it could attract goods and services tax and stamp duty, depending on the type of assets involved and the states in which they are registered. Companies should also evaluate availability of tax neutrality under domestic laws and double taxation avoidance agreements between India and the jurisdictions in which the foreign company is incorporated.

Additionally, since the reverse flip would involve unwinding or restructuring of a foreign company as well, the structuring of the entire transaction would have to be done keeping in mind the laws of the foreign jurisdiction where the foreign company is incorporated, especially around procedures for liquidation, buybacks, mergers, shareholder approvals, reporting requirements, tax obligations on exit and restructuring, and local foreign exchange and investment restrictions and conditions.

Further, given the cross-border nature of reverse flip transactions, the structuring would have to be done in compliance with foreign exchange laws of India. Compliance with pricing guidelines, sectoral caps, entry routes and other attendant conditionalities would have to be ensured. In structures where funds are repatriated into India, the inflow of capital would have to comply with rules on the source and end-use of funds. The Reserve Bank of India and authorised dealer banks will examine whether the remittances meet the prescribed guidelines and whether they could potentially fall within the ambit of round-tripping.

In addition to regulatory compliance, practical issues such as valuation, employee stock option plan migration, and contract/ intellectual property assignment also arise. Incentive plans tied to the foreign entity may need to be restructured or replaced under the Indian entity. Existing customer and vendor contracts, along with intellectual property agreements, may require novation or reassignment to ensure continuity. The entire process must be carefully sequenced to minimise business disruption and regulatory risk.

Conclusion

As the Indian startup ecosystem matures and domestic capital markets evolve, the rationale for maintaining offshore corporate structures is increasingly being questioned. The rise of reverse flips underscores a broader shift in sentiment, both regulatory and strategic, towards strengthening India’s role as a global hub for innovation and investment.

That said, reverse flipping is not merely a symbolic homecoming. It is a legally complex, multi-jurisdictional exercise that must account for tax liabilities, regulatory compliance, valuation norms, sectoral restrictions, and the legal frameworks of foreign jurisdictions. No single structure fits all, and each reverse flip must be tailored to the company’s operational, legal, and investor dynamics.

When carefully planned and executed, a reverse flip can offer significant advantages — including a simplified ownership structure, reduced compliance burdens, and better alignment with a company’s principal market and operations. As Indian regulatory and financial ecosystems continue to develop, reverse flips are poised to become a defining feature of the next chapter in India’s startup journey.

This website is owned and operated by Spice Route Legal, and is exclusively meant to be a source of information on the firm, it’s practice areas, and its members.

It is not intended and should not be construed as any form of advertisement, solicitation, invitation or inducement of any sort from the firm or its members.

Spice Route Legal does not warrant that any information provided on the website is accurate, complete or updated, and further denies liability for any and all loss or damage caused to the user as a result of their reliance on the content provided.

The information made available on this site must in no way be relied upon, or construed, as legal advice. If you need legal assistance, we recommend you seek help from competent counsel licensed to practice and advise in the relevant jurisdiction.